“Shall we be famous?” Ted Hughes recalls asking the Ouija board he and Sylvia consulted, only to be stunned by Sylvia’s violent reaction:

And give yourself to the glare? Is that what you want?

Why should you want to be famous?

Don’t you see – fame will ruin everything.

Had she heard, he wonders, some premonitory still small voice that he had missed?

Fame will come. Fame especially for you.

Fame cannot be avoided. And when it comes

You will have paid for it with your happiness,

Your husband and your life.

Birthday Letters (1998)

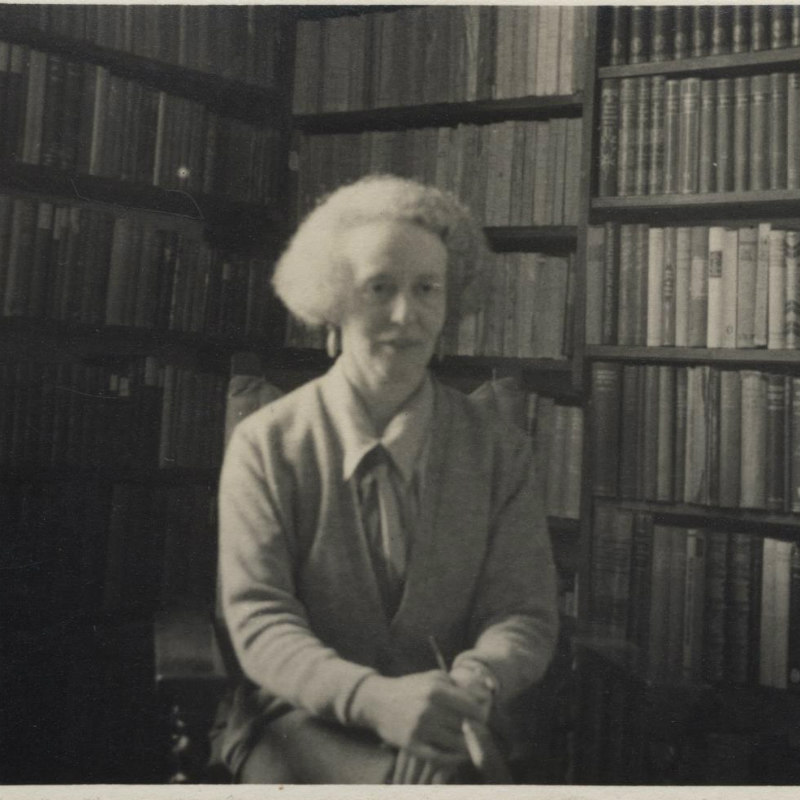

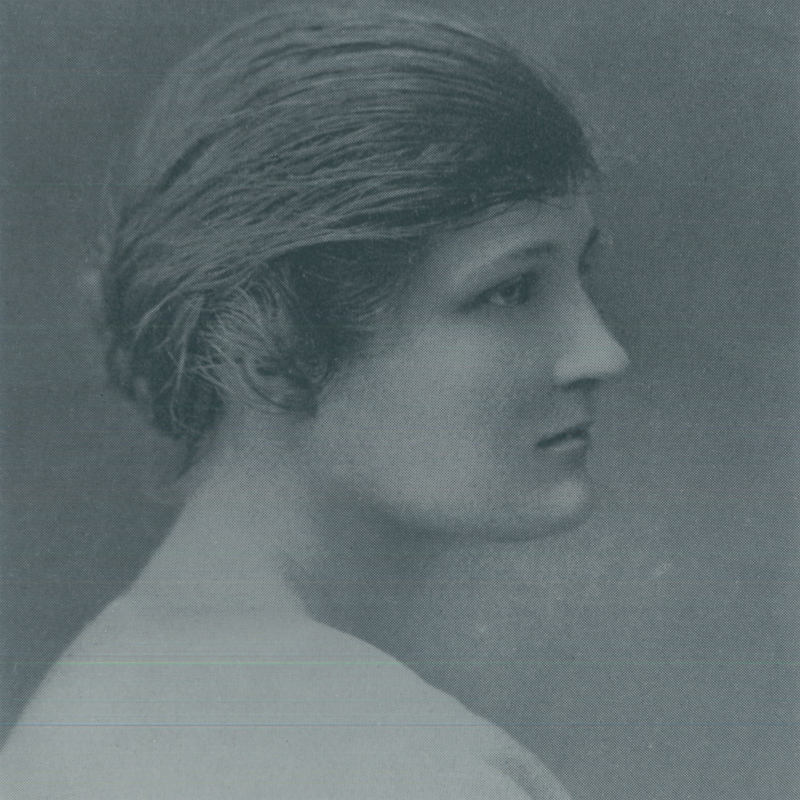

Yet Sylvia did want, seek out, the ‘fame’ for which she paid that terrible price. “Hurl yourself at goals above your head” she exhorts herself in her journal; or, a few months later, “If only I knew how high I could set my goals”. The imperatives accumulate. She had determined to be a writer long before the now legendary meeting with Ted Hughes in Falcon Yard. She was, Ted recognised, “twice as ambitious as Emily [Bronte]”. Their marriage – a collaboration of ‘radioactive’ intensity, haunted by the past, astrologically ‘fated’ – was a truly rare conjunction of talent and commitment. Stars of their generation, they shared an unsurpassed single-mindedness about their art. Sylvia became, as she wanted, “one of the Makeris: with Ted.” The work of both stands among the greatest poetry of the twentieth century.

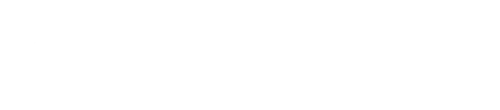

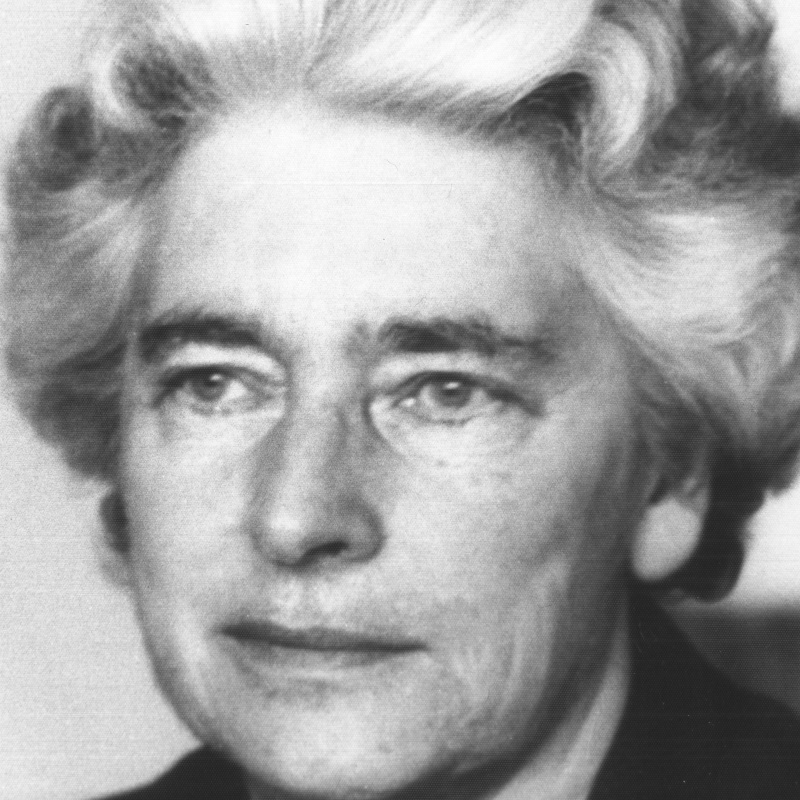

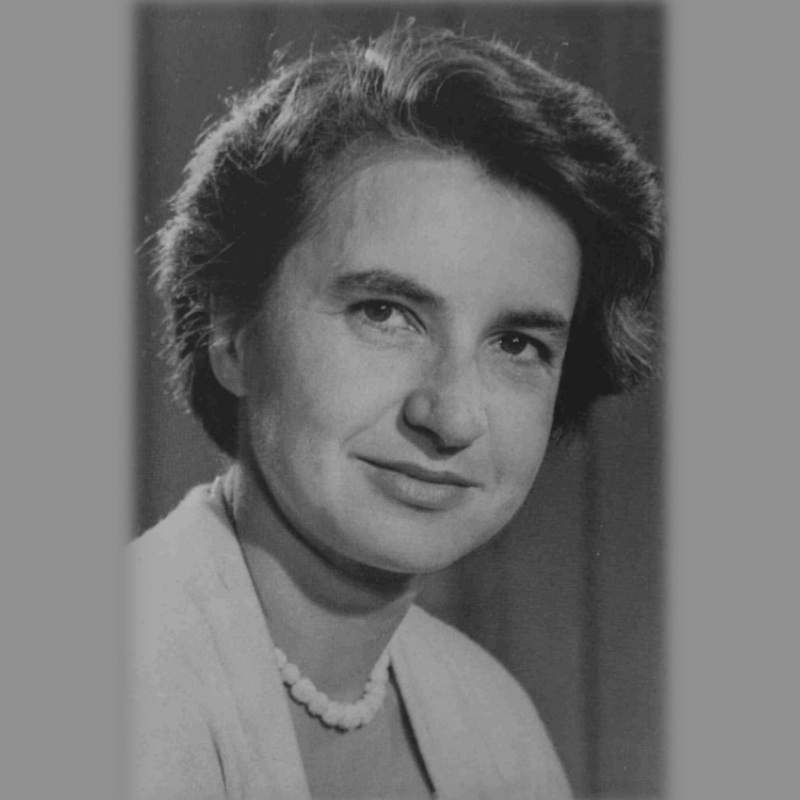

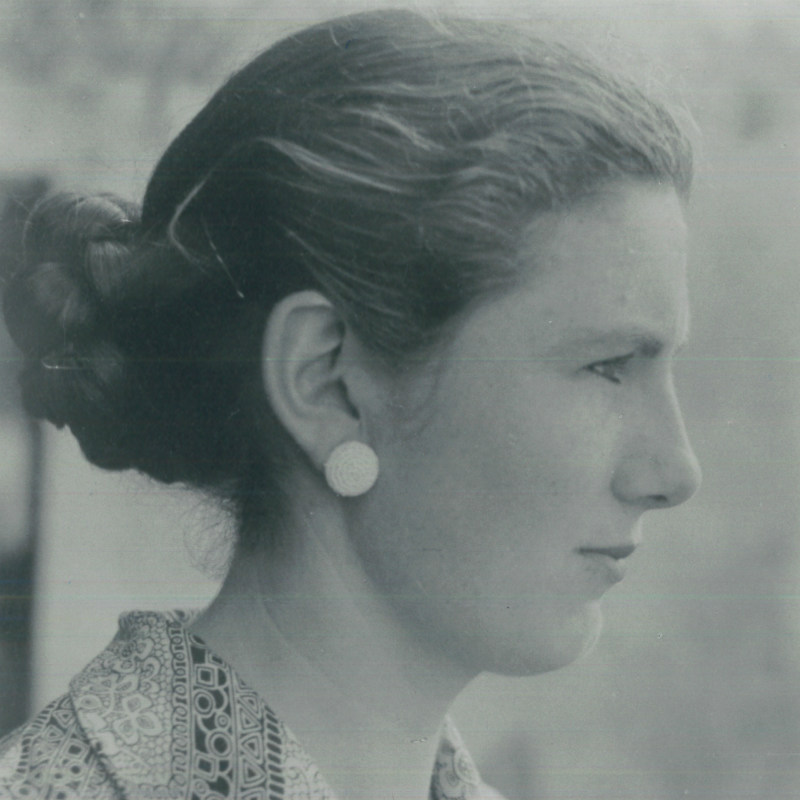

The salient biographical facts figure in what Sylvia Plath called “the dialogue between my Writing and my Life”. She was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1932. The death of her father when she was eight left marks that she was to cultivate and collate devastatingly with later experiences. An exemplary Alpha record took her to Smith College, where her student years were extended by a breakdown leading to a suicide attempt and ECT treatment. She went on to win a Fulbright scholarship that brought her to Newnham in 1955. At Cambridge she read English as an ‘affiliated’ student, taking Part II of the Tripos in two years and graduating with an honours degree in 1957. On 26 February 1956, at the launch party for the St Botolph’s Review, she met Ted Hughes. They married four months later on James Joyce’s ‘Bloomsday’: only her mother was present. Sylvia returned to Smith in the fall of 1958 to teach freshman English, Ted writing and teaching at the University of Massachusetts. They had expected a ‘vagabond’ life as writers, but Sylvia’s pregnancy drew them back first to London, and then to Court Green, an old farmhouse in Devon. The Colossus & Other Poems was published in 1960, followed in 1961 by her novel The Bell Jar (under a pseudonym) and an anthology American Poetry Now, then in 1962 by a radio play, Three Women. Sylvia was writing with personal immediacy about pregnancy, childbirth, babies, bee-keeping, mythologies, country rituals – topics springing from direct encounters of imagination and body. She possessed what Ted Hughes called “an instant special pass to the centre, [that] she had no choice but to use.” Her daughter Frieda said she “used every emotional experience as if it were a scrap of material that could be pieced together to make a wonderful dress.” By 1962 the marriage was breaking. Sylvia moved to a flat in 23 Fitzroy Road, once Yeats’ London house, with the two small children. Alone, ill with ‘flu, she struggled to re-establish an independent social circle. On 11 February 1963 in the coldest winter of the century, after taking precautions to protect the children from the effects of gas, she put her head in the oven. She was thirty.

Most of the extraordinary stream of poetry written almost daily over that last year was discovered after her death. Ted Hughes’ edition of Ariel came out in 1965 followed by Crossing the Water and Winter Trees in 1971, and more. Then the prose writings in 1977. Her Collected Poems (1981) won the Pulitzer Prize for literature, the first to be awarded posthumously. The best poems (as Claire Tomalin says) “stop your breath with their spare, intense, thrilling images. They are crafted as carefully as Cellini’s pieces.” Sylvia Plath knew her own growing power and technical originality: she made herself a vehicle of both revenge and celebration in ways that carry a lasting reach. Hers was indeed a hard claim to fame.

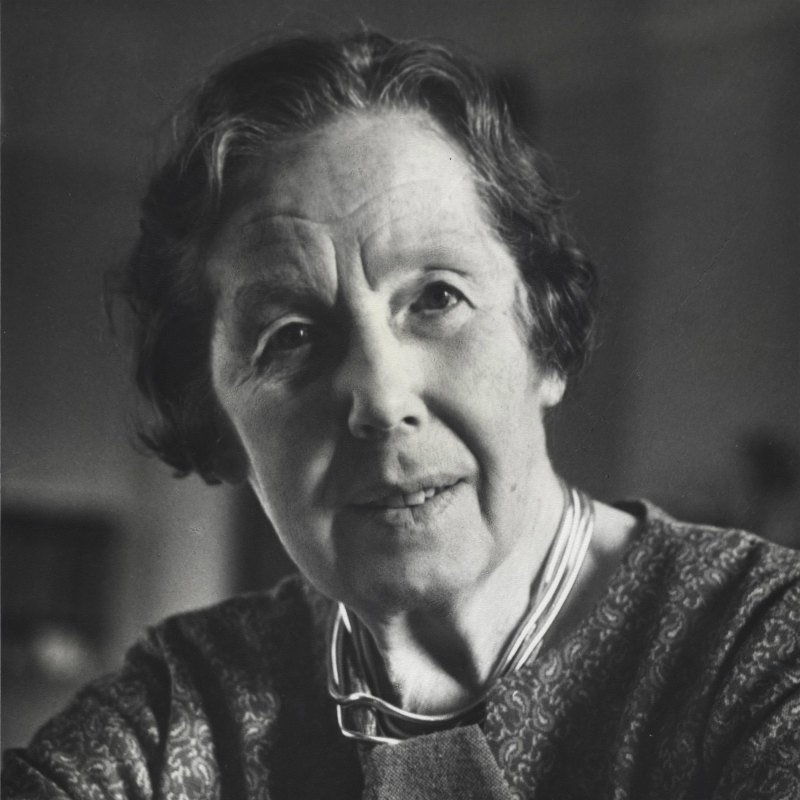

Jean Gooder, 2008

To read further:

- Myers, Lucas, Crow Steered Bergs Appeared: A Memoir of Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, Proctor’s Hall Press, Sewanee, Tennessee, 2001.

- Feinstein, Elaine, Ted Hughes: The Life of a Poet, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2001.

- Sylvia Plath, Foreword by Margaret Drabble, The Guardian series Great poets of the 20th century, No. 3, 2008.